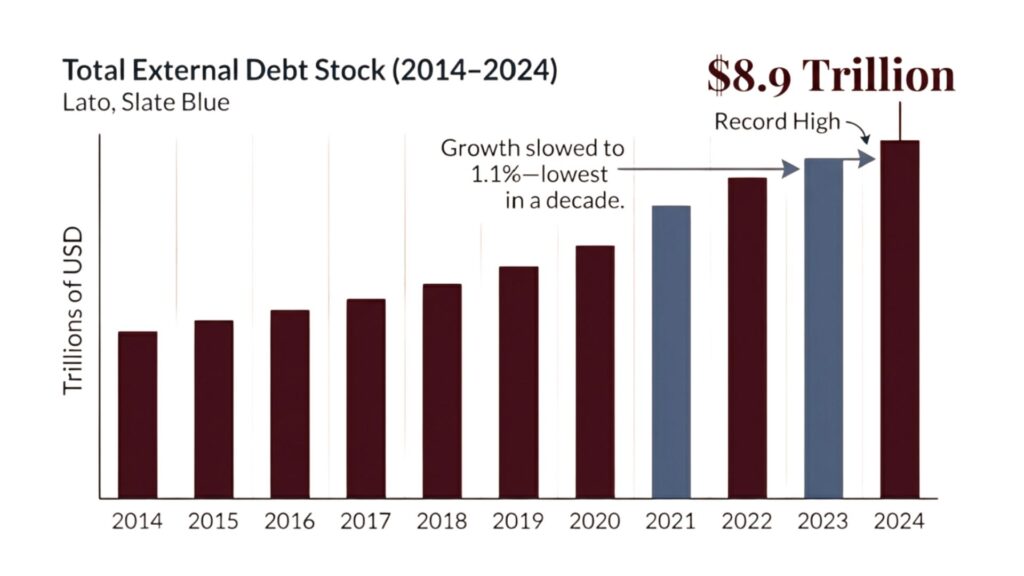

Navigating the Debt Paradox – A paradox is playing out across developing economies. On one hand, global inflation is abating and the oppressive interest rates of the past five years have begun to ease, suggesting that crushing debt service burdens might start to shrink. Yet this surface-level relief masks a grim reality. As the World Bank’s 2025 International Debt Report reveals, the total external debt stock of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) reached a new record of US$8.9 trillion in 2024. These nations paid a staggering US$415 billion in interest alone, contributing to an unprecedented financial undertow.

The upheavals of the early 2020s have triggered a historic financial outflow. Between 2022 and 2024, about US$741 billion more flowed out of developing economies in debt repayments than flowed into them as new financing—the largest debt-related outflow in over 50 years. This reversal is diverting critical resources from development and putting immense pressure on the world’s most vulnerable populations, creating a high-stakes environment where a temporary easing of financial conditions may not be enough to avert a deeper crisis.

The State of Development Debt: A Staggering New Record

The total external debt of low- and middle-income countries reached a new record of US$8.9 trillion in 2024, despite a significant slowdown in debt accumulation. These nations now face the highest debt service burdens in decades, forcing them to divert critical funds away from essential development priorities like health, education, and infrastructure.

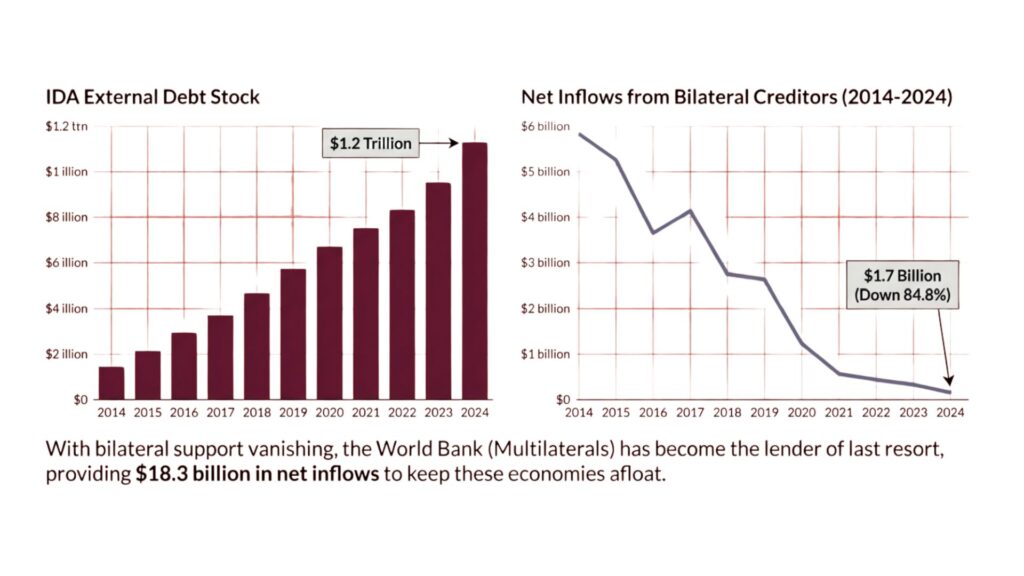

While the growth of total external debt slowed to just 1.1% in 2024, the underlying figures remain alarming. The debt stock for the 78 most vulnerable countries—those eligible for assistance from the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA)—also hit a record US$1.2 trillion.

A Seismic Shift in the Creditor Landscape

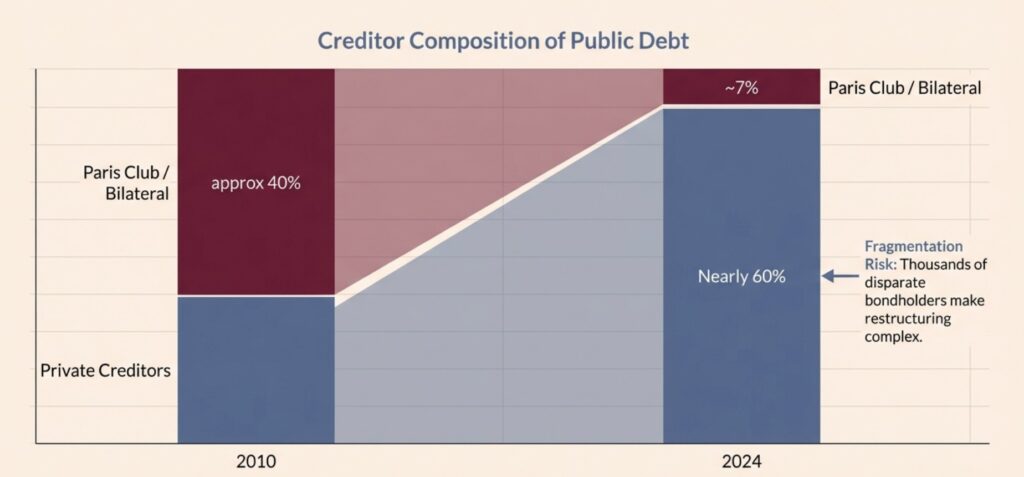

This financial strain is exacerbated by a global debt architecture that remains dangerously outdated. Designed for an era when developing economies owed most of their external debt to official creditors like the World Bank and the handful of high-income economies comprising the Paris Club, this structure is ill-equipped to handle modern realities of credit risk and financial stability.

The Rise of Private Creditors: Today, private creditors, primarily bondholders, account for nearly 60% of the long-term public and publicly guaranteed (PPG) debt of developing economies. Decision-making authority has shifted away from a small group of official lenders and is now dispersed among millions of individual bondholders. This fragmentation complicates coordination and amplifies risk, forcing countries to pay steep premiums in reopened bond markets, as seen in the recent wave of high-yield issuances.

The Waning Influence of Traditional Lenders: In a stark reversal, debt owed to Paris Club creditors—the longtime overseers of the global debt-restructuring system—now accounts for only about 7% of the total. This fragmented and decentralized creditor base makes debt restructuring efforts in the 2020s exceptionally sluggish and complex.

2024 Market Dynamics: A High-Stakes Gamble on Risky Capital

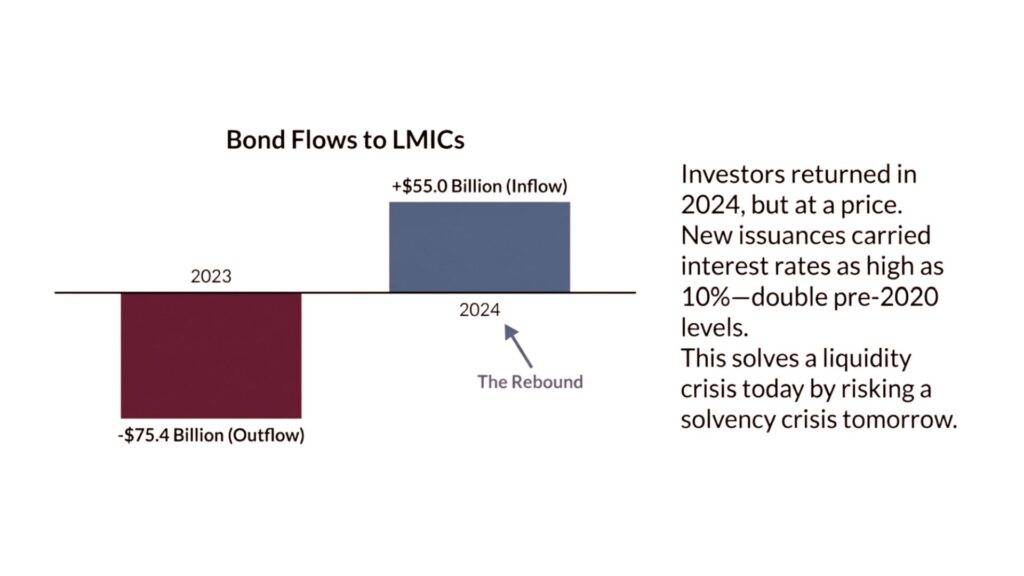

The reopening of capital markets in 2024 presented a double-edged sword for developing economies. While it provided much-needed financing, the nature of this capital—expensive short-term bonds and domestic debt that crowds out the private sector—deepens the paradox rather than solving it.

Bond Markets Reopen, But at a Steep Price In 2024, bond flows to LMICs saw a dramatic reversal, shifting from a US$75.4 billion outflow in 2023 to a US$55.0 billion inflow. This turnaround reflects renewed investor confidence and allowed several countries to issue new bonds to finance budget deficits or pay off maturing debt. However, this new capital came at a steep price. The interest rates on these new issuances were as high as 10%, roughly double the pre-2020 rate, locking vulnerable economies into years of high-cost borrowing.

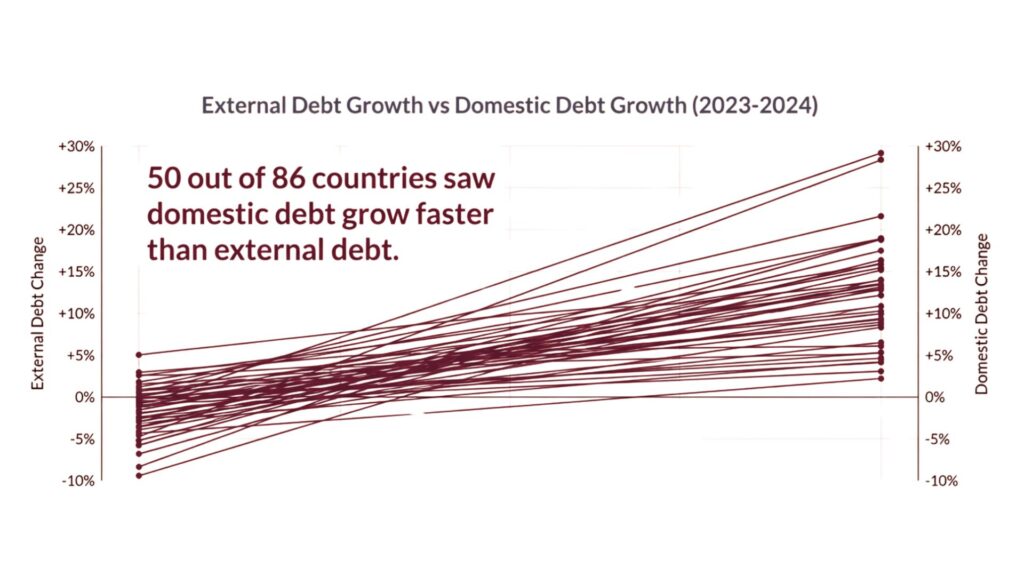

The Pivot to Domestic Debt To fill financing gaps, many developing countries turned inward. Among 86 countries with available data, 50 saw their domestic government debt grow faster than their external debt. While this strategy can mitigate foreign exchange risk, it carries a significant downside. It often comes at the expense of the private sector, as local commercial banks load up on government bonds instead of lending to businesses, stifling productive investment. Furthermore, this strategy swaps foreign exchange risk for another vulnerability: domestic debt often carries shorter maturities, exposing governments to greater rollover risk in volatile local interest rate environments.

A Tale of Two Lenders: Multilateral Support vs. Bilateral Retreat

In 2024, multilateral creditors provided the largest share of net debt inflows, acting as a critical lifeline. The World Bank, for instance, provided a record US$18.3 billion more in financing to IDA-eligible countries than it received in repayments from them. This support underscored the essential role of multilateral institutions during a period of intense financial strain.

In sharp contrast, official bilateral creditors retreated. These government and government-related entities collected US$8.8 billion more in principal and interest payments than they disbursed in new financing. This withdrawal by key government lenders left many developing nations with fewer affordable financing options, forcing them to turn to more expensive and riskier sources of capital.

The Human Cost of Unsustainable Debt

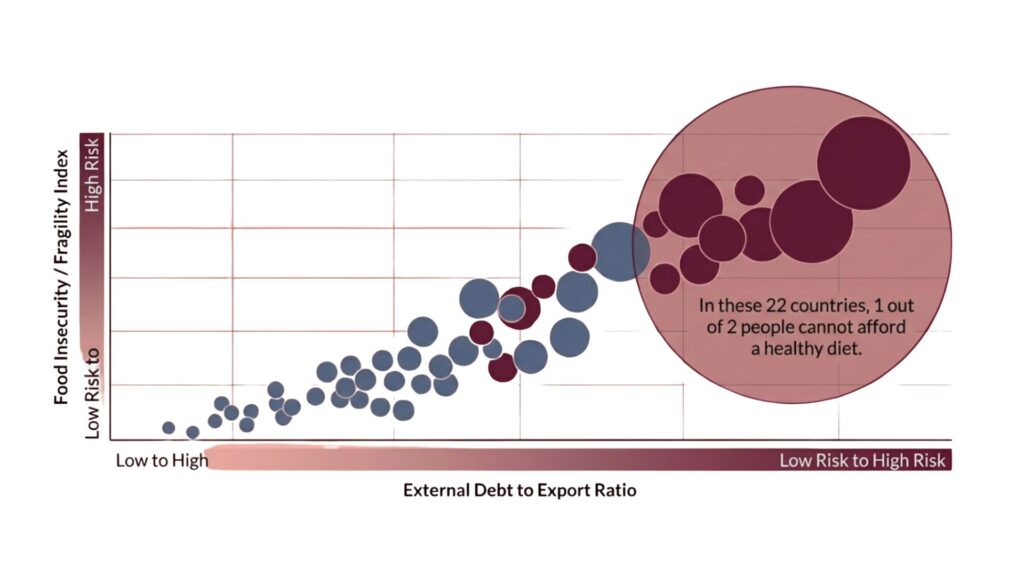

The financial figures translate into a steep human toll. Among the 22 most highly indebted countries, a shocking one out of every two people cannot afford the minimum daily diet necessary for lasting health. The record US$415 billion paid in interest payments in 2024 represents money that could have been used for critical development goals. These funds could have helped trim the rising ranks of out-of-school children, improve primary health care, and electrify rural villages, but were instead diverted to service an ever-growing mountain of debt.

Conclusion: A Precarious Path Forward

The current easing of global financial conditions offers temporary “breathing room,” but it is not a solution. The World Bank’s report warns that policymakers must use this window to enact urgent reforms, putting fiscal houses in order and reducing sovereign risks to spur productive investment. Without modernizing outdated debt management frameworks and accelerating restructuring processes, vulnerable countries risk “sleepwalking into a larger calamity tomorrow.” Key external risks, from trade volatility to geopolitical conflict, loom large, threatening to turn this period of fleeting relief into a prelude for a much deeper, more intractable crisis if decisive action is not taken now.

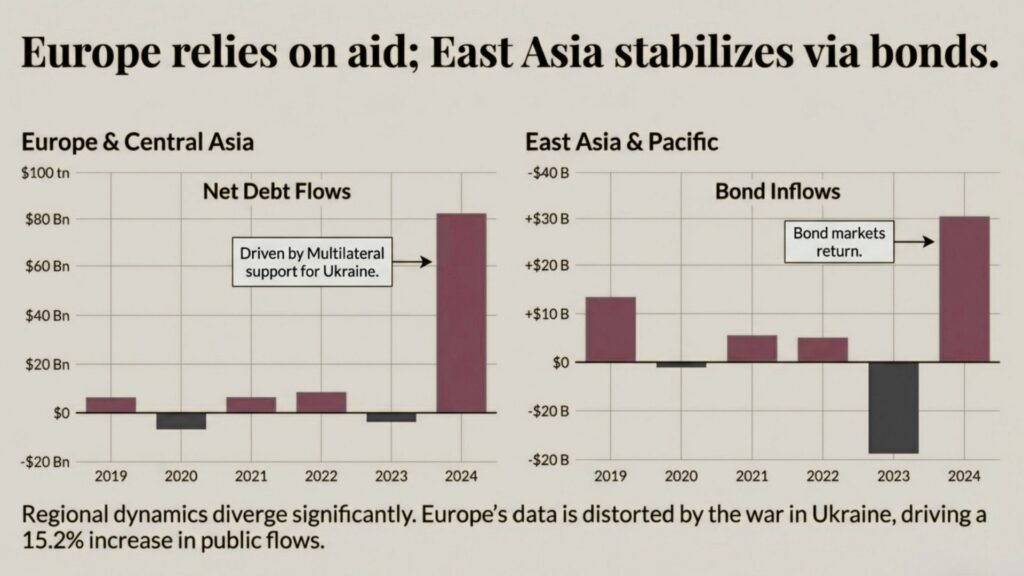

Europe relies on aid; East Asia stabilizes via bonds

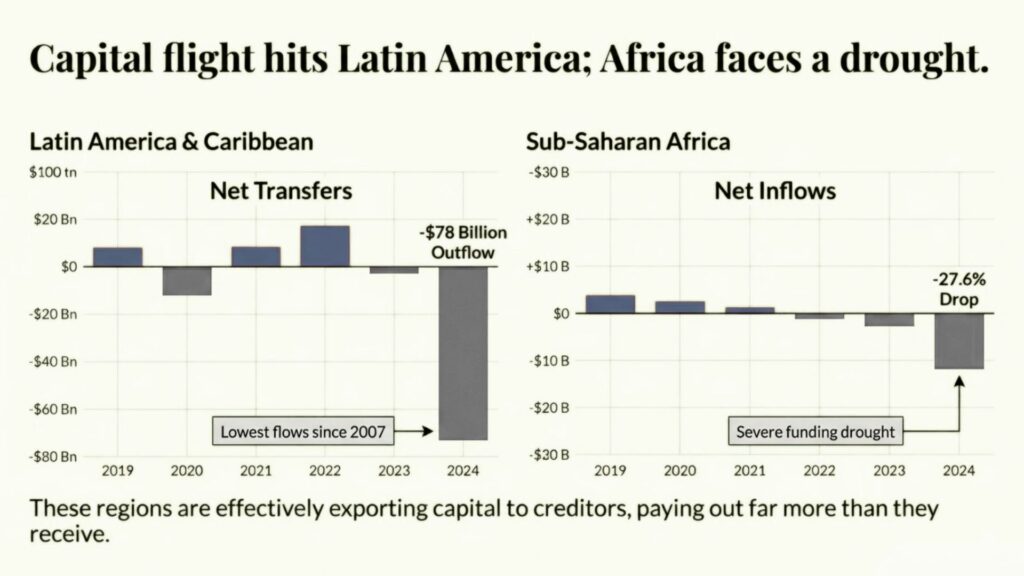

Capital flight hits Latin America; Africa faces a drought.

https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/7c0dbf75-2bd7-4ae3-9db9-91318290c781

답글 남기기